These notes contain some of the reasoning behind the proposals of [McCarthy, 1987] to introduce contexts as formal objects. The present proposals are incomplete and tentative. In particular the formulas are not what we will eventually want, and I will feel free to use formulas in discussions of different applications that aren't always compatible with each other. [While I dithered, R.V. Guha wrote his dissertation.]

Our object is to introduce contexts as abstract mathematical entities with properties useful in artificial intelligence. Our attitude is therefore a computer science or engineering attitude. If one takes a psychological or philosophical attitude, one can examine the phenomenon of contextual dependence of an utterance or a belief. However, it seems to me unlikely that this study will result in a unique conclusion about what context is. Instead, as is usual in AI, various notions will be found useful.

One major AI goal of this formalization is to allow simple

axioms for common sense phenomena, e.g. axioms for static blocks world

situations, to be lifted to contexts involving fewer

assumptions, e.g. to contexts in which situations change. This is

necessary if the axioms are to be included in general common sense

databases that can be used by any programs needing to know about the

phenomenon covered but which may be concerned with other mattters as

well. Rules for lifting are described in section ![]() and

an example is given.

and

an example is given.

A second goal is to treat the context associated with a particular circumstance, e.g. the context of a conversation in which terms have particular meanings that they wouldn't have in the language in general.

The most ambitious goal is to make AI systems which are never

permanently stuck with the concepts they use at a given time because

they can always transcend the context they are in--if they are

smart enough or are told how to do so. To this end, formulas

![]() are always considered as themselves asserted within

a context, i.e. we have something like

are always considered as themselves asserted within

a context, i.e. we have something like

![]() . The

regress is infinite, but we will show that it is harmless.

. The

regress is infinite, but we will show that it is harmless.

The main formulas are sentences of the form

Contexts are abstract objects. We don't offer a definition, but we will offer some examples. Some contexts will be rich objects, like situations in situation calculus. For example, the context associated with a conversation is rich; we cannot list all the common assumptions of the participants. Thus we don't purport to describe such contexts completely; we only say something about them. On the other hand, the contexts associated with certain microtheories are poor and can be completely described.

Here are some examples.

![]() is the assertion that John McCarthy is at

Stanford University in a context in which it is given that

is the assertion that John McCarthy is at

Stanford University in a context in which it is given that ![]() stands for the author of this paper and that

stands for the author of this paper and that ![]() stands for

Stanford University. The context

stands for

Stanford University. The context ![]() may be one in which the symbol

may be one in which the symbol

![]() is taken in the sense of being regularly at a place, rather than

meaning momentarily at the place. In another context

is taken in the sense of being regularly at a place, rather than

meaning momentarily at the place. In another context ![]() ,

,

![]() may mean physical presence at Stanford at a certain

instant. Programs based on the theory should use the appropriate

meaning automatically.

may mean physical presence at Stanford at a certain

instant. Programs based on the theory should use the appropriate

meaning automatically.

Besides the sentence ![]() , we also want the

term

, we also want the

term ![]() where

where ![]() is a term. For example, we may need

is a term. For example, we may need

![]() , when

, when ![]() is a context that has a time, e.g. a context

usable for making assertions about a particular situation. The

interpretation of

is a context that has a time, e.g. a context

usable for making assertions about a particular situation. The

interpretation of ![]() involves a problem that doesn't

arise with

involves a problem that doesn't

arise with ![]() . Namely, the space in which terms take values

may itself be context dependent. However, many applications will not

require this generality and will allow the domain of terms to be

regarded as fixed.

. Namely, the space in which terms take values

may itself be context dependent. However, many applications will not

require this generality and will allow the domain of terms to be

regarded as fixed.

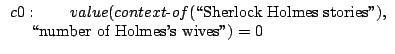

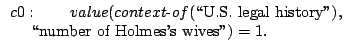

Here's another example of the value of a term depending on context:

|

|