AN EVERYWHERE CONTINUOUS NOWHERE DIFFRENTIABLE FUNCTION

John McCarthy, Princeton University

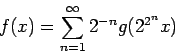

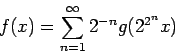

The following is an especially simple example. It is

The function ![]() is continuous because it is the uniform limit of

continuous functions. To show that it is not differentiable, take

is continuous because it is the uniform limit of

continuous functions. To show that it is not differentiable, take

![]() , choosing whichever sign makes

, choosing whichever sign makes ![]() and

and

![]() be on the same linear segment of

be on the same linear segment of ![]() . We

have

. We

have

1.

![]() for

for ![]() , since

, since ![]() has

period

has

period

![]()

2.

![]()

3.

![]()

Hence

![]() which goes to infinity with

which goes to infinity with ![]() .

.

The proof that the present example has the required property is simpler than that for any other example the author has seen.

Weierstrass gave the example

![]() for

for ![]() and

and

![]() which is discussed in

Goursat-Hedrick Mathematical Analysis.

which is discussed in

Goursat-Hedrick Mathematical Analysis.

A complete discussion of functions with various singular properties is given in Hobson, Functions of a Real Variable, volume II, Cambridge, 1926.

2006 January note: I was tempted to dig up this 1953 note of mine and put it on my web page by reading The Calculus Gallery by William Dunham. This excellent book includes the first proofs of a number of important theorems, including Weierstrass's proof that his function has the required properties. Dunham's version of Weierstrass's proof is six pages of what Dunham describes as difficult mathematics. Since my proof is 13 lines of what I consider easy math, I decided to copy my old note and discuss it. Dunham recounts that the famous mathematicians Hermite, Poincare and Picard all expressed themselves as repelled by Weierstrass's ``pathological example''. I'm sure that by the time I was born in 1927, such functions were no longer regarded as repellent. My own opinion is that most everywhere continuous functions, in some suitable sense of most, are nowhere differentiable.

Remarks:

1. To prove a function ![]() differentiable at

differentiable at ![]() , one must show that no

matter how

, one must show that no

matter how ![]() goes to zero,

goes to zero,

![]() approaches a limit. To prove

approaches a limit. To prove ![]() non-differentiable at

non-differentiable at ![]() , one need

only find a sequence of values of

, one need

only find a sequence of values of ![]() for which the limit

doesn't exist.

for which the limit

doesn't exist.

2. If ![]() is to be represented as the sum of a series of continuous

functions, it suffices to bound the terms by a suitable positive

terms,

is to be represented as the sum of a series of continuous

functions, it suffices to bound the terms by a suitable positive

terms, ![]() in our case. Then

in our case. Then ![]() is sure to be everywhere

continuous. It doesn't matter how fast the successive terms wiggle.

is sure to be everywhere

continuous. It doesn't matter how fast the successive terms wiggle.

3. In our case, the terms are

![]() . The

. The ![]() grows fast enough to overcome the

grows fast enough to overcome the ![]() damping.

damping.

4. I would expect

![]() to be nowhere differentiable

for most any initial

to be nowhere differentiable

for most any initial ![]() .

.

5. However, the particular ![]() makes the proof easy, because the

periodicity kills the higher terms of the series for

makes the proof easy, because the

periodicity kills the higher terms of the series for ![]() ,

and using

,

and using ![]() for the argument allows the

for the argument allows the ![]() th term to go to

infinity and dominate the earlier terms of the series. It seems lucky

in whatever sense luck exists in mathematics.

th term to go to

infinity and dominate the earlier terms of the series. It seems lucky

in whatever sense luck exists in mathematics.